The deep ocean is not a good place to find food.

In the crushing darkness thousands of meters below the surface, nutrients are scarce, and life operates in slow motion. Those animals that survive do so on scraps that drift down from above—a process marine biologists call "marine snow."

And in this desolate space, we see the remarkable problem-solving power of evolution. The challenges are numerous:

How do species adapt to these harsh conditions?

How do they find enough energy to reproduce?

How do they carve out living areas in this vast, cold emptiness?

I’m glad I asked, because there's a remarkable phenomenon that transforms this barren landscape into an oasis of life. A phenomenon that begins with death.

When a blue whale—the largest animal ever to exist on Earth—dies and sinks to the ocean floor, something extraordinary happens. The massive carcass, up to 200 tons, becomes what scientists call a "whale fall."

It’s miraculous.

In 1987, scientists in the submersible "Alvin" stumbled upon a 21-meter-long blue whale skeleton during a routine dive. What they found wasn't a scene of desolation, but rather a "biological carpet"—a thriving ecosystem of bacteria, worms, and specialized organisms that had turned death into a celebration of life.

In the North Pacific alone, researchers have documented whale falls supporting at least 12,490 organisms across 43 different species. Many of these creatures exist nowhere else on Earth; they've evolved specifically to capitalize on these enormous windfalls of nutrients. Desolation transformed.

The fallen dead whale is a jackpot for deep-sea creatures, and not a rare one. Whale falls may occur as frequently as every ten miles on the seafloor, creating hundreds of thousands of oases worldwide. They deliver about a thousand years' worth of food in one fell swoop.

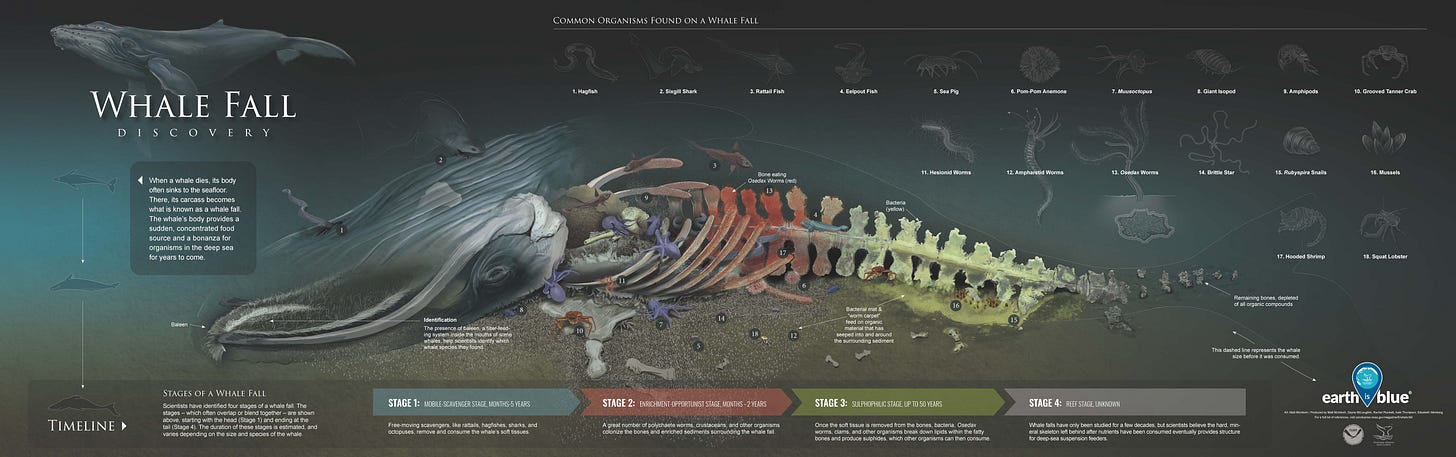

In all, there are four distinct phases in a whale-fall ecosystem:

Mobile-Scavenger Stage: Scavengers, hagfish, gigantic sleeper sharks, and larger crustaceans consume most of the blubber and muscle. This stage can last up to 1.5 years.

Enrichment-Opportunist Stage: In this stage, smaller organisms such as osedax worms (called "zombie worms") and crustaceans dig through the sediment to find bits of decomposing tissue and feed on the blubber. This stage lasts from months to 4.5 years.

Sulphophilic Stage (formerly Self-Fulfilling Stage): This stage is the longest. Bacteria consume the fat in the bones and produce hydrogen sulfide. This feeds deep-sea shellfish, mussels, clams, octopuses, and snails, which in turn power other microscopic organisms. This stage is one of the longest, lasting between 50 to 100 years. The period makes studying these phenomena difficult.

Reef Stage: The final stage of the whale-fall ecosystem in which the remaining bones are fed on by suspension feeders (Bivalves, barnacles and sponges to name a few.)

Beyond the bustling ecosystems they create, also notable is the carbon the whale fall sequesters. As the massive carcass descends, it carries with it a vast amount of carbon, locked within its tissues, and ultimately deposited on the deep seafloor. Over decades, as the whale fall decomposes, much of this carbon becomes buried in the sediment, effectively locking it away for centuries, if not millennia. In a world grappling with climate change, these deep-sea graveyards quietly contribute to the planet's carbon cycle, highlighting yet another vital, if often overlooked, service provided by these magnificent creatures, even in death.

For marine biologists, whale falls represent a profound ecological principle. These massive creatures don't just drive life and ecosystems while alive - they transform into entirely new ecosystems after death, serving as "biodiversity generators" where organisms from different energy-rich seafloor habitats can mingle. The boundary between organism and environment blurs in a way that challenges our understanding of life itself.

The next time you contemplate the wonders of evolution, remember these underwater oases. They're proof that in nature, nothing is wasted, and even the end of one magnificent life can support thousands of others for decades to come. Through their deaths, these ocean giants create nurseries of biodiversity in Earth's most challenging frontier.

And that's definitely a Good Thing.