I once planned and took a trip to a reasonably swank hotel in Mexico. It was featured in the movie “When a Man Loves a Woman” and the stay there was magical and fun.

When we planned this trip, we were surprised by the (relatively) cheap prices in both airfare and accommodations. “It’s the rainy season” we were warned. But the hotel looked so good!

When we arrived the weather was (except for one day) truly lovely and amazing. One dinner we met the hotel’s owner. It was a nice talk, and eventually we got to the worries we had and were given about the weather. The owner looked at us and said (something along the lines of), “You know how they tell the weather these days for this part of Mexico? One guy in Mexico City looks West out his window and reports on what he sees.”

Now, the owner was probably exaggerating, but that it how weather forecasting once was. And now, weather forecasting is amazing! And it’s getting better.

Around 650BC, Babylon, weather forecasting is thought to have been based on cloud patterns and astrology.

Around 340BC, Greece, 340 B.C., Aristotle wrote Meteorologica, a philosophical treatise that included theories about the formation of rain, clouds, hail, wind, thunder, lightning, and hurricanes. Many of Aristotle’s claims were erroneous, although it was not until about the 17th century that many of his ideas were formally dismissed or overthrown.

1643, Italy, Evangelista Torricelli invents the barometer.

The 1920s, United Kingdom, British mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson grasps that you didn’t need a precise snapshot of all weather in all places to make predictions. Instead you could split the globe up into a grid with each quadrant representing a gigantic column of air. He envisaged an army of humans with pencil and paper in hand, dispatched to each square, calculating approximate answers for the equations in their section and regularly swapping numbers with the people in the neighboring squares, so that the mathematical winds could blow from one corner of Earth to another.

June 4, 1944, off the Coast of France Coast, Group Captain James Martin Stagg, a meteorologist for the British military, convinces a reluctant General Dwight D. Eisenhower that D Day should be postponed.A few hours later, Stagg had better news. Allied weather stations were reporting a ridge of high pressure that would reach the beaches of Normandy on June 6th. The weather wouldn’t be ideal, but it would be good enough to proceed. Eisenhower gave the order to reschedule the invasion.

We use computer models instead of Richardson’s army, and the computers are informed by massive streams of data collected by satellites and oceanic buoys.

This dynamic is incredibly accurate, and getting more so. In 2015, a six-day forecast was as good as its three-day forecast was in 1975. By 2025, we can expect to detect high-impact events (like Hurricanes) two weeks into the future.

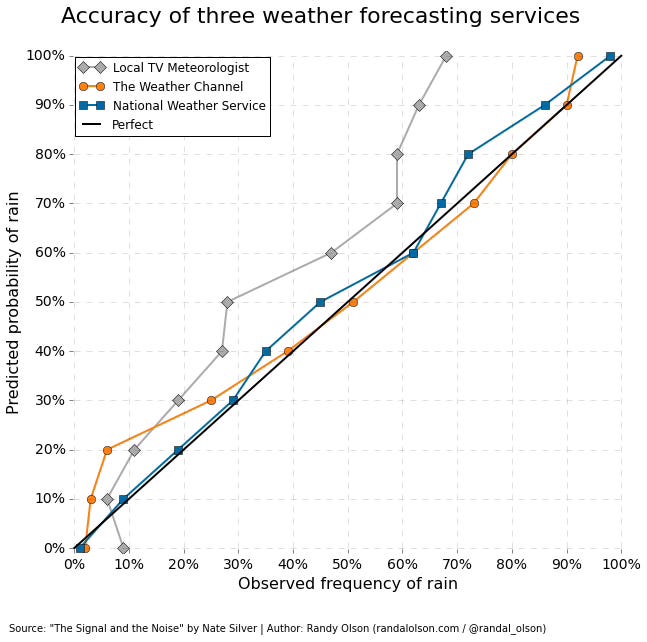

So no more jokes about weathermen. Our weather predictions are pretty amazing.

And that’s a good thing.