Forgiveness

Divine goodness

To err is human, to forgive divine.

Now, I’m not sure who among us would consider genocide just a little error, but this is a Good News missive!

Roughly thirty years ago the Rwandan genocide took place. Since then one might expect hurt and vengeance permeate those aggreived. I’m sure those feelings do, but what has also come to the fore is forgiveness. It’s amazing.

A lot of this comes via a wonderful story in the Guardian that goes much deeper into those noble people who are actually forgiving some heinous acts, but I find this all so good and wonderful I’m also writing about it.

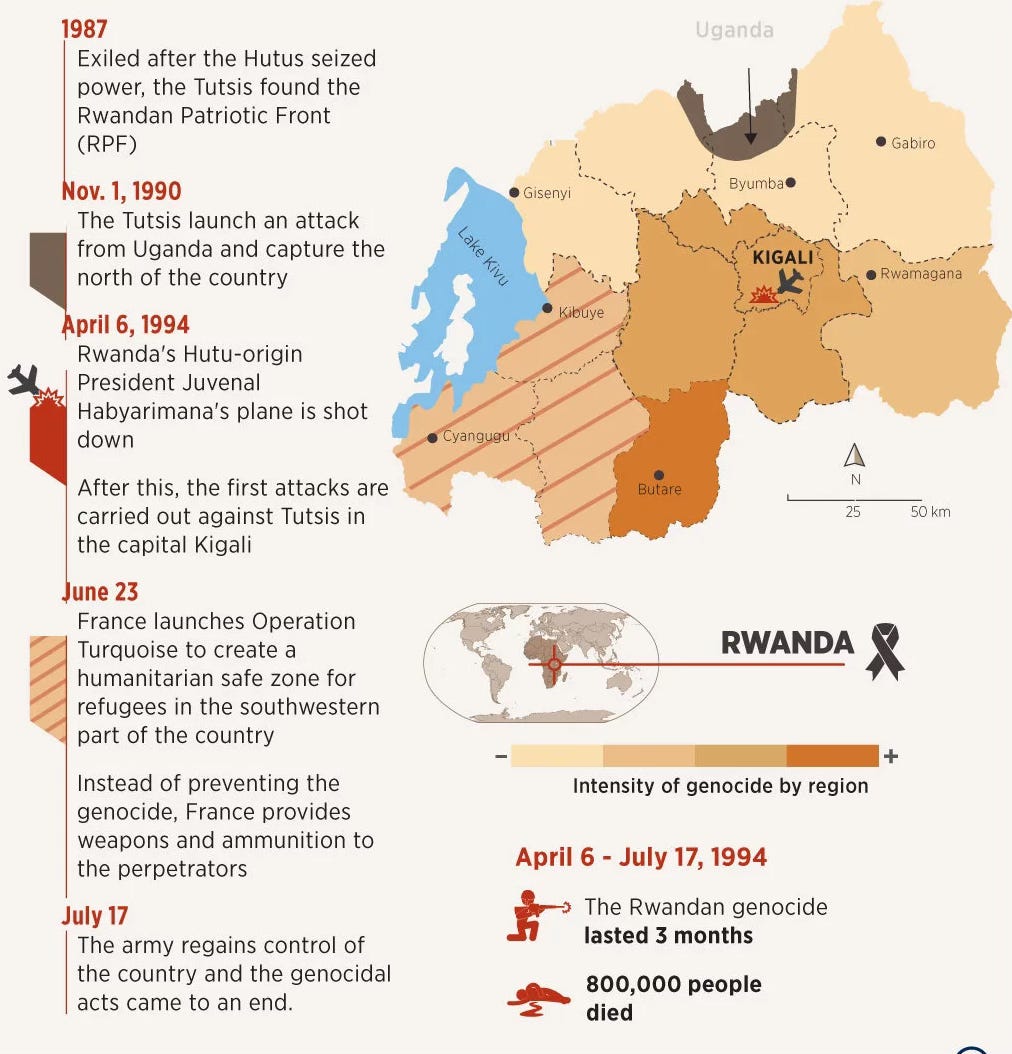

This infographic basically encapsulates the horrible Rwandan genocide where, in 100 odd days, between 500,000 and 1,000,000 people were killed.

Those numbers are staggering.

But

Wonderful and extraordinary reconciliations are taking place across the central-African country. Unthinkable as it may seem, partnerships have formed between executioners and survivors, and within families that were torn apart by the massacres.

In Karongi, where 9 out of every 10 Tutsis were killed, "people came to apologize," depicts 70-year-old whose very family was among those decimated.

"I told them, 'I will never forgive you.' I never thought I would exchange another word with those people." Yet now she feels "a glimmer of joy."

Every genocide has to come to an end. One way or another. And when it does, what happens?

Those who experienced it bear their scars and bury their dead. Those who perpetrated it face punishment or go unpunished.

And then? And all that's left is for people to attempt to coexist again. But how? It’s hard, it’s full of distrust, it’s probably going to be painfully slow and arduous, but holy jeepers in this case it is oh so inspiring.

Never in history has a country known so many deaths in so little time. Over half a million lives were taken in 100 days, mainly Tutsis, but also Hutus mistaken for or protecting Tutsis. Most did not perish from military violence, but from the machetes and studded clubs of neighbors and acquaintances. Executioners and victims spoke the same language, shared the same Christian religion and culture.

How does one overcome such trauma, especially in an impoverished country with limited mental healthcare? In 2005, Dutch sociotherapist Cora Dekker developed an affordable and effective method with the Anglican diocese of Byumba. This approach, first used in Western clinics to treat soldiers and asylum seekers, was transformed into volunteer work led by trained local therapists.

In Rwanda, it is called Mvura Nkuvure: "I heal you, you heal me."

This wind of forgiveness and mutual understanding blowing over the country is a symbol of hope for humanity. Despite the horror, reconciliation is possible when hearts open to compassion. Rwanda is showing the way towards a future of lasting peace.

So profound! so inspiring! So hard!I I did graduate work alongside a Rwandan student, and will never forget the tenacity and openness of his journey.