Imagine a world where the fear of an anonymous snakebite is significantly reduced, where the worry of 'could it be poisonous?' loses its grip on a parent's mind. There are over 600 different venomous snakes on Earth, but we may be looking at a single solution for this multi-variant problem. How? It's a possible reality born from the most unlikely of circumstances: the extraordinary and perilous efforts and suffering of one man have unlocked a critical key in the quest for a universal antivenom.

It only took one man to be bitten approximately 200 times by venomous snakes.

Why this is a good thing follows:

Friede's extraordinary ordeal, as unsettling as it sounds, holds the key to a profoundly good thing: the potential for a universal antivenom. To many, Tim Friede's quest is mind-boggling and jarring. Twenty years, 200 bites, 16 venomous snakes. And so is the result: his blood, incredibly, contains antibodies capable of neutralizing the venom of multiple, diverse snake species. Detailed in the journal Cell, this achievement, almost the stuff of legends, represents a significant step in addressing a dire global health crisis that claims over 100,000 lives and leaves hundreds of thousands more maimed and impaired on a yearly basis."

Antivenoms do exist, but access to them is limited and typically species-specific, meaning that identifying the snake responsible for a bite is crucial – often an impossible task for victims. Take the case of two cobras, Indian cobra (Naja naja) and Thai cobra (Naja kaouthia), there are parts of Southeast Asia and Thailand in which both Cobras live. But the snakes different venom compositions and require distinct antivenoms for effective treatment of bites.

Traditional antivenoms have other, more esoteric issues, some are derived from animals like horses or sheep, and can trigger severe allergic reactions in patients. This is why the development of a universal antivenom is so great. A safer, more accessible, and ultimately much more elegant and effective solution.

I’m taking a little liberty with using the word elegant. Let’s return to the curious case of Tim Friede. Scientists at Centivax, led by Jacob Glanville, were drawn to Friede's case after learning of his (cough cough) unusual campaign. Glanville, who himself grew up in Guatemala, immediately seized upon the potential of harnessing the human immune response to create broadly acting antibodies. If we have universal vaccines, why not universal antivenins. Friede was a game-changer.

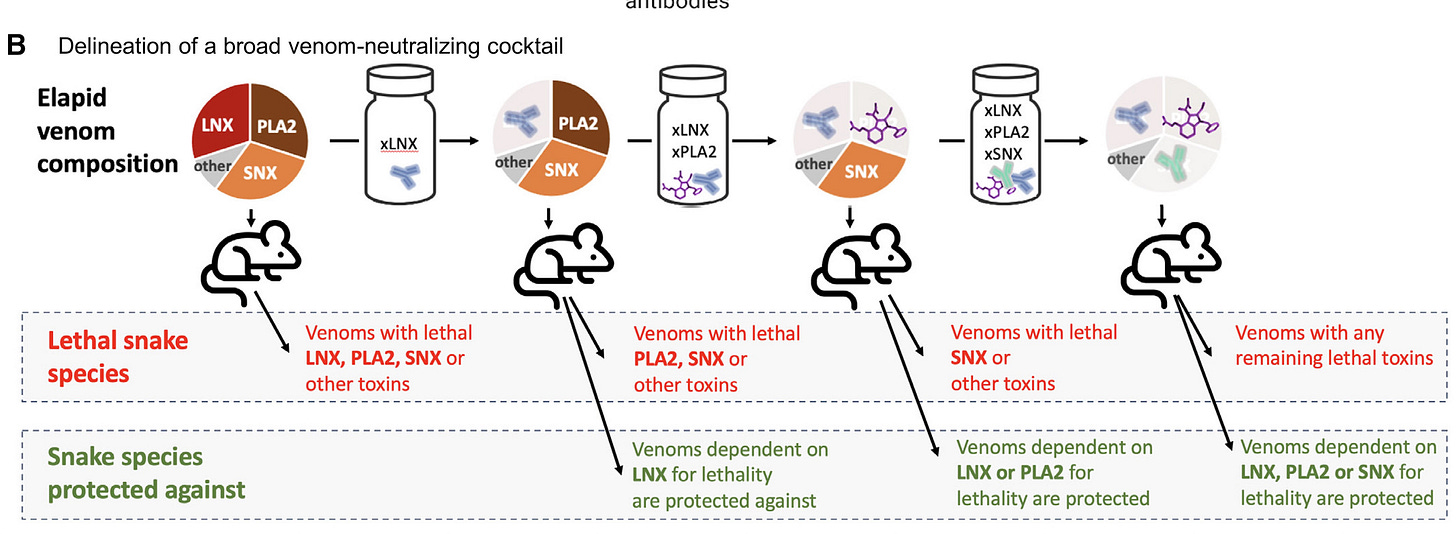

Analysis of Friede's blood quickly centered on two particularly potent antibodies, LNX-D09 and SNX-B03. The former seemed to be singularly effective in neutralizing venom from six deadly snake species. That number more than doubled, offering full protection against 13 species, when these two antibodies were combined with a drug called varespladib. This cocktail included some of the deadliest and most prominent highly venomous snakes.

Snake venoms are complex cocktails of toxins. Evolution works against us (humans) in this regard. Venoms vary because of multiple factors including location, age, diet, and process. Elapid venoms attack neurons, others damage tissues. Some do both. Some do other things.

And this is why Friede’s quest for being bitten has resolved into something special. The antibodies found in Friede's blood target common, previously unknown, aspects of toxins, such as the interfaces between neurotoxins and their host target receptors. Common aspects allows them to neutralize a broader range of venoms.

While rigorous (and pricey!) clinical trials are still ahead, the implications of this research are profound. A single antivenom could revolutionize snakebite treatment, particularly in regions where access to healthcare and specific antivenoms is scarce. It could simplify first aid, reduce the risk of allergic reactions, and ultimately save lives.

Tim Friede was bitten 200 times. He also self-injected diluted venom over 600 times.

This is imaginative. Yes.

It’s hardcore. Definitely.

It’s dangerous. Indeed.

But this unconventional and undeniably risky pursuit has, against all odds, paved the way for a future where the threat of a venomous snakebite carries far less fear.

That’s a good thing.